Leg And Wing Fractures In Wild Birds And How I Repair Them

Ron Hines DVM PhD

“Why is your header photo a parrot with a broken wing and leg? That’s not a wild bird in the United States is it? In the USA I thought that all parrots live in cages or are escapees.“ Well, this parrot wants you to know that she has always been a native bird in the Rio Grande Valley of Texas. Read more about that here:

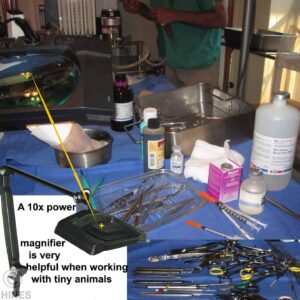

Dear Reader, The photos and links just above describes some of the methods I use to repair broken legs in wild birds. What is below is an overflow of photos that relate to various other articles of mine on avian fractures along with short explanations about them. Because I no longer own an animal hospital, I have to keep my wildlife rehabilitation expenses low. I also have had to adapt to performing my surgery without trained assistance. I do not charge anyone for my services. Texas Parks & Wildlife drops these animals off at my door. But they have never considered contributing to their care.

All of these animals have been sedated with ketamine and diazepam . An alternative is a tiletamine/zolazepam (=Telazol®/Tilzolan®/Zoletil®) combination. I give some injured bird local pain blocks of xylocaine® as well.

Birds that cannot extend their wings will have difficulty standing when they first attempt to. They are best kept in a quiet, darkened room and towel-padded enclosure until they are fully awake. They overcome their balance problems within 24 hours or less.

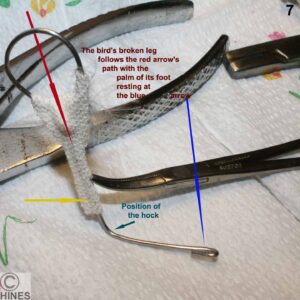

Over the years, I have attempted to fix avian leg fractures with intramedullary (within the bone) acrylic shuttle pins, external Kirschner apparatus with Methyl methacrylate supports, Jonas cross pins, etc. None have produced final results that exceeded modified Thomas splints like the one pictured above. Bone plates, screws, rods and the like are great for humans, dogs and cats. They allow almost immediate use of the fractured limb. But the thin-walled, fragile bones of birds and the small body size of the majority of flighted birds do not lend themselves to those techniques.

Malleable (easily bent) stainless steel wire is available in a variety of diameters (gauges). When it is to be used within the body, it needs to be of surgical grade. When it is not, it can be any convenient non-stainless metal that is bendable and appropriate the the bird’s size. I use the medical grade for everything because I have accumulated a large supply of it from hospital discards and have become used to its qualities, strength and limitations. Various hospital one-time-procedures are manufactured from more rigid stainless steel wire or hollow tube – items such as spinal tap needles, intravascular retrievers, etc. Although tubes tends to crimp at the bends, sometimes it can be accomplished and produce a splint that is exceedingly light weight but still strong. I have never found a source of aluminum wire of the proper diameter and malleability for external use as splint material. For dogs and cats, thicker aluminum rod it is readily available. In a pinch, coat hanger wire,bent around a round tube as seen in this photo works well for external splints for larger birds:

Tape comes in all degrees of stickiness and rigidity. The ones available at WalMart and Target tend to be the ouchless varieties that are unsuitable to my needs in birds. The ones I find best are in the orthopedic and cast-room discards of my local hospitals. They also form the surrounds of some disposable stoma bags. In tiny birds, Tegaderm™ film with thin cardboard or flat toothpick supports works well. No matter how it is done, it needs to be checked quite frequently to be sure it is not abrading skin or restricting circulation to the lower extremity. Frequent adjustments and replacements are commonly required. Only chewing and gnawing birds are likely to attempt to remove it.

When I was employed by the NIH , I used a surgical microscope to operate on mice.

Adjust perches and cage appurtenances (“stuff”) to accommodate handicapped birds during their recover.

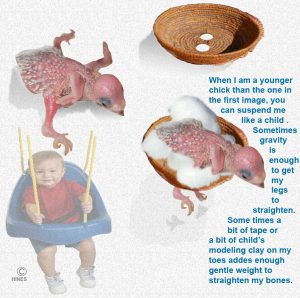

The blue vinyl-clad wire that I chose for this bird was in one of our hospital’s discard boxes, also a very sticky large-fiber tape that you see applied. This bird will end up in a deep “nest” with two leg holes cut in the bottom. Similar to this one:

The same mystery tape used to give padding to pressure points on the splint.

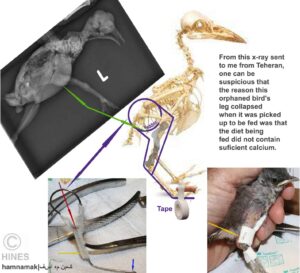

The young street pigeon in Tehran, shown in the X-ray above did well when a splint was applied to its leg and it was given proper care and nutrition (powdered eggshells millet, cracked corn, sorghum and fine grit). It is not the mockingbird or it’s splint that are also shown in the photo. I worked together with the young man who had rescued the pigeon and his veterinarian online. Some of the photos you see in these articles I take expressly for people with injured birds who live far away :

Be creative. I have always called these medical wooden sticks “brightwood sticks”. You will know them when you see them and you will find them in craft stores. The two ends are the problem. The photo above was taken before they were padded. The ends of “poky” splints and steel pins can often be wrapped with a bit of Gorilla™ tape to keep them blunt and less traumatic to the skin.

Park pigeons can live successfully without return to their full flying abilities. They just have to be able to roost high enough to avoid dogs and feral cats. Immobilizing the injured wing using the first 5 primary wing feathers of the uninjured wing to support the same feathers on the injured one – along with a shoulder strap of twine to keep shoulder alignment identical is quite effective in allowing simple fracture of a broken wing to heal. Fractures that expose bone require more complex procedures

The same goes for shore birds like this heron that are large enough to intimidate dogs, cats, raptors and coyotes. You need to choose your release areas wisely.

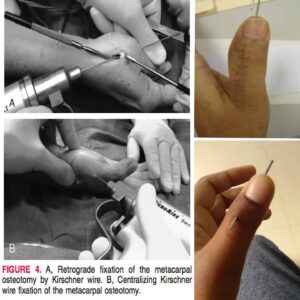

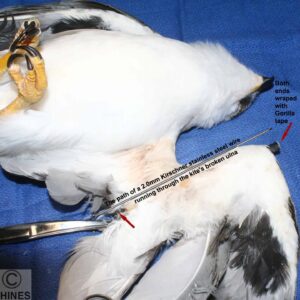

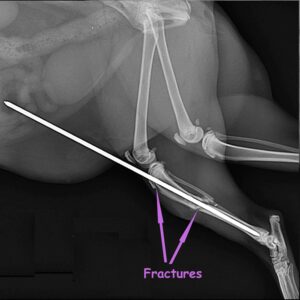

One of my favorite intramedullary bone pins for wing fractures in larger birds are the same ones used by hand physicians and rheumatologists:

The DOT Clamp

Every winter Canadian winds reach deep South Texas. They come in spurts – generally bringing colder weather. It only became a calamity for Texas pelicans when the Texas Department of Transportation installed tall concrete barriers at the center median of the highway passing through the Laguna Atascosa Wildlife Refuge. DOT’s motivations were good. Party-goers to South Padre Island, driving home tipsy, had frequent head on collisions. However the barriers cause strong downdrafts on those windy winter days that are too strong for the pelicans to resist. The result is that they crash on one or the other side of these center barriers and are hit by the next passing automobile. This has gone on for years and years. DOT, Texas Parks & Wildlife and the USFWS prefer to ignore the situation. “What Problem? We’ll just drop them off at Hines’ house”. For a while they did. However the injured pelicans required 3-4 pounds of fish a day. The birds were unappreciative of my presence and I am getting too old to throw a cast net. Now they go to our local zoo where their eventual fate is not revealed. It is December now in Texas. This email came in today:

These are kind hearted people – angels who risk their lives at night on a busy highway attempting to get these pelicans across before they are injured. God Bless them. But during the time I accepted these wing injuries I had plenty of pelicans to develop the DOT Clamp procedure.

It is also possible to thread an 18 gauge stainless wire between the radius and ulna bones of the wing and the two metacarpal bones. However I find the completely external DOT clamp as effective or moreso. Read about both procedures in detail here.

This is a young bobcat that was hit by a car while crossing a Texas road. The bone pin has yet to be sheared off just below the knee. Only enough will protrude to grasp and extract the pin once the bone (tibia) has healed sufficiently. Applying external Thomas splints like this one is still a common procedure at your local animal hospital. A steel bone pin, as in the second photo, is often required as well. A veterinary orthopedic surgeon might preferred a bone plate and screws. Their principals are the same as mine – custom fabrication, proper positioning, no restriction of blood flow and very frequent checkups, and adjustments. It is just the very small size, fragility and rapid growth of my fast-growing patients that makes good outcomes more challenging and choices more limited.

Dear reader, Besides your donations, Visiting the products that Google chooses to display on this webpage helps me pay the cost of keeping this article on the Web. As you know, sites like mine that are not designed to make money are getting harder and harder to find. Best wishes, Ron Hines

Dear reader, Besides your donations, Visiting the products that Google chooses to display on this webpage helps me pay the cost of keeping this article on the Web. As you know, sites like mine that are not designed to make money are getting harder and harder to find. Best wishes, Ron Hines